Floating Wetlands in Lake Union

Nearshore floating wetlands provide food and rearing habitats for juvenile salmon, and improve water quality by intercepting storm water, trapping sediment, sequestering metals, and reducing harmful algal blooms.

However, more than 30% of Puget Sound coastlines and over 75% of Seattle’s shorelines have been converted to urban conditions, including ports, marinas, docks, bulkheads, armored revetments, roads, railways, docks and other uses.

Floating wetlands are an innovative approach to restore the wetland and shoreline habitat functions of providing food sources and refuge for salmon, and to help reverse degraded urban water quality.

EarthCorps, in partnership with the University of Washington’ Green Futures Lab, is participating in a study to better understand the impact of floating wetlands on salmon and water quality within the Puget Sound region.

Kasey’s Story:

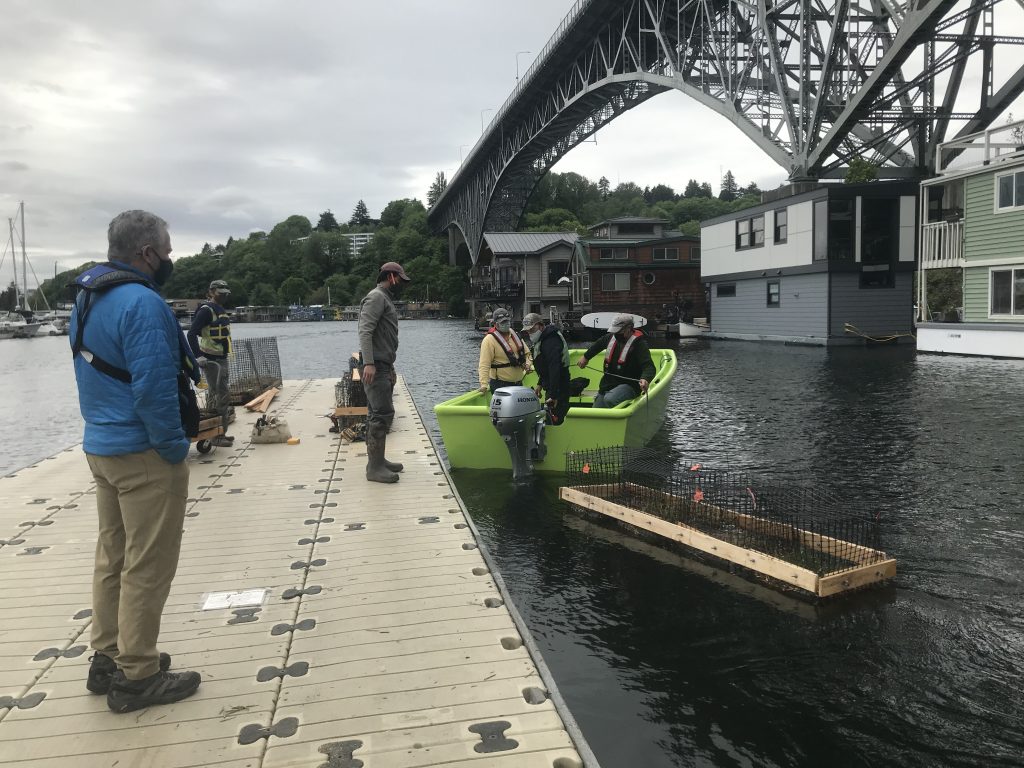

My crew recently had the opportunity to construct and install floating wetland modules in Lake Union in Seattle. This project was different from our typical crew work. Instead of spending our days grubbing out blackberry or pulling ivy, we used industrial sewing machines and drills. Instead of working in pockets of forest we did most of our work in the old hatchery on the UW campus. It was a really interesting project with a lot of potential. In many ways, this project was everything I hope for in a field project:

- Community support. There was a lot of support for this project and we had the opportunity to work with community volunteers;

- Partnership with indigenous communities. The focus of the project was on planting the culturally significant Ka’qsxW or sweetgrass (common three-square bulrush) and the project engages indigenous youth to work on the project.

- A focus on salmon restoration. The focus of the floating wetlands project is to improve water quality and to provide habitat for juvenile salmon; and

- Creative and adaptive solutions to environmental problems. So much of our waterfront space has been hardened (paved over or “developed” to maximize economic benefits and reduce flooding). As a result, the nearshore wetlands that provided food and rearing habitats for juvenile salmon and improved water quality by intercepting stormwater, trapping sediments, sequestering metals, and reducing harmful algal blooms, are no longer there to perform those environmental functions. Installing floating wetlands is an innovative and fairly low-cost alternative to restore wetland habitats along urban shorelines and it’s exciting to think about the possibilities for expanding this model to other areas.

As Corps members, we come into this work with energy and excitement for the possibilities. We build partnerships and dream about the long-term impact of our work, and we work to develop creative and innovative solutions to the problems before us.

At the same time, we grapple with questions around whether our work will truly have the impact we hope it will. For example, most of the floating wetland modules involved a fair amount of plastic. Plastic netting is used to hold it all together and/or keep geese from eating all the plants and zip ties are used to secure it all together. Sure, the plastic is durable and will hold everything together for a long time, but it feels odd to try to solve one environmental problem while contributing to another, especially given all the detrimental impacts that plastic waste has on our waterways. A smaller part of the project did involve testing some biodegradable modules in a different part of Lake Union but still involved the installation of plastic goose netting and the bulk of the research project focused on the modules made with plastic.

Then there is the issue of funding. When we try to think on the grand time line of forests and landscapes, we are often stopped by the timetables of funders. For example, the current funding for the floating wetlands project is limited. Therefore, unless further funding is acquired, the wetland modules we spent so many hours building and installing will be removed.

The next time you’re walking across the Fremont Bridge, or biking beneath it on the Burke Gilman trail, or wandering across the pedestrian bridge to the museum of History and Industry, I invite you to look out for some wetland plants floating in the water. Send some encouragement and love to the sweetgrass, the rushes, the sedges, and the juvenile salmonids we hope they will support. Dream an expansive future for them. Then push and prod, interrogate, and dismantle the systems of capitalism and white supremacy and exploitation that continue to limit our work. Don’t stop until we reach that expansive future.

*The project was part of a University of Washington PhD thesis, funded by a grant through the Rose Foundation, built upon work done by the Sweetgrass Urban Shorelines Working Group, and included in-kind support from the Na’ah Illahee Fund and United Indians of All Tribes Foundation