Celebrate the Rain

“We are water people!” I told the crew with a burst of Pacific Northwest pride. It was the fifth downpour of the week. Seven of us were standing by the side of a road in Everett. We were soaking wet.

At our feet, a steady stream of oily water was racing along the curb. The water came from nearby roofs, streets, sidewalks, and even lawns. It was headed toward a storm drain, then into a series of pipes. Eventually it would travel to the Snohomish River, and then out to the Puget Sound. On its journey across the city’s hard surfaces, the water picked up heavy metals, oil, fertilizer, and pet waste – unsavory companions on its trip to the Sound.

Watching this oil slick run toward the drain, we were struck by a simple but fundamental question: “How do we handle this much rain?”

Luckily, there’s an answer...

Dig a hole

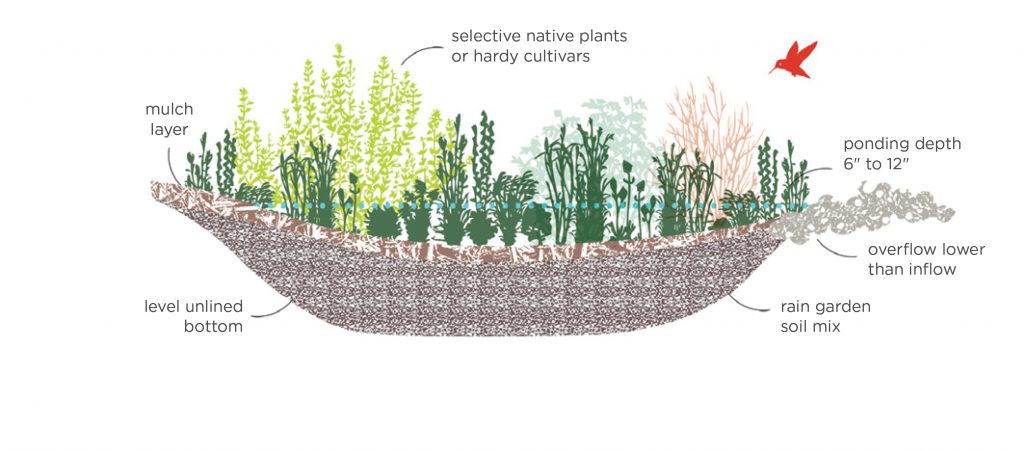

The answer starts with a hole. A hole can hold a lot of water. Inside the hole, layers of special soils and plants absorb and clean the water.

Behind where we were standing in the pouring rain, excavators had recently finished digging a giant hole. Not just any hole. This hole has specifically designed dimensions, angles, and slopes. Its exact location has been calculated to collect all of the rain that falls on a 2½ acre area. (That’s about the size of two football fields, including the end-zones.)

The hole has a system of pipes. Inflow pipes help direct the water into the hole. An outflow pipe channels any overflow in the event that there is too much rain for the garden to hold. In that case, excess water will exit through the outflow pipe and connect into the city’s conventional stormwater pipes.

Graphic by Stewardship Partners

Turn the Hole into a Garden

EarthCorps’ role was to transform this giant hole into a garden. The crews had their work cut out for them.

For this garden, they hauled the equivalent of ten dump trucks (100 cubic yards) of a bioretention mix, a blend of sand and compost, to fill the hole. This special bioretention soil mixture allows water to infiltrate into the ground, while providing organic matter and nutrients for plants to thrive.

The bioretention soil needs to be “sculpted” to fit the contours of the hole, being careful not to compress it. If you tamp it down or step on it, the dirt compresses, and the water cannot pass through as easily.

Next, we layered a two-inch deep cap of mulch over the soil. The mulch suppresses weeds and keeps in needed moisture for the plants during the dry summer.

Finally, we planted 1,000 wetland sedges and shrubs. The hole became a garden.

Get ready for the rain!

When rainwater flows into the garden, the soil microbes and wetland plants will go to work. We specifically chose these plants because of their ability to break down the pollutants that rainwater carries into the garden. The water will slowly percolate into the ground and recharge the groundwater. Once established, the garden will be beautiful year-round. And it will really shine when it rains.

Rain Gardens

Some people grow gardens to harvest food. Our garden has some edible plants, but its most important purpose is to harvest the rain. Gardens like these can hold a huge amount of water, which helps abate flood risk during heavy rains.

Rain gardens help filter toxic runoff, which is critical to protecting aquatic wildlife, including our beloved salmon and shellfish. The aesthetic design of rain gardens creates a colorful public space for the community to enjoy.

Interested in learning more about how rain gardens protect aquatic life in Puget Sound? Watch this movie by The Nature Conservancy about the work of EarthCorps alumna Dr. Jenifer McIntyre.

A Regional Movement

EarthCorps designs, builds and maintains rain gardens. Our work helps power a movement across the Puget Sound region to clean up toxic runoff.

In 2016, EarthCorps partnered with The Boeing Company and Pierce Conservation District to raffle off a rain garden to residents of the Key Peninsula. Scott and Gretchen Snider-Bassett won the raffle. They welcomed the opportunity to increase their property value by creating a delightful garden that also protects threatened shellfish beds in Vaughn Bay. Read about their experience in the Key Peninsula News.

Rain gardens are just one part of the growing portfolio of “green” approaches to managing runoff. Permeable pavement, green roofs, water harvesting systems and bioswales are a few examples of innovations that welcome the rain. Healthy urban forests reach for raindrops – slowing down, absorbing, and filtering water that falls on their leaves and soil. Even backyard evergreen trees can make substantial contributions to water treatment in residential areas.

In the Pacific Northwest, we appreciate rain. After all, we are water people.

EarthCorps’ Stormwater Initiative is generously supported by The Boeing Company, Bullitt Foundation, and RealNetworks Foundation.

All project photographs taken by Crew Leader Cory Burke.